In first part of this article I’ve answered two major questions related to microfrontend architecture — what is it and what is it for. In second part I’ve described how does it work from end user’s perspective. This part, third and last one, covers principles, tools and processes that help us create and maintain our microfrontends.

That was general overview of how all these things work together. Let me now show you the process from developer’s perspective. How do they create microfrontends in our world?

Standardization and automation

As I mentioned before, main problem with microfrontends approach to frontend development would come out of its main feature — autonomy of development teams causing fragmentation of development. Dan Abramov correctly points this out by his analogy to game development. However, this assumption is, in my opinion, a result of big misunderstanding related to concept of microfrontends.

Jules Glegg, Riot Games employee who also participated in Twitter discussion I’m referring to, put it in simple words: adapting this approach does not mean that development teams are not supposed to talk to each other anymore. As a matter of fact, I would argue that they are now supposed to communicate and align even more, as there are plenty of things to agree upon. Therefore, in order to fight this risk, our microfrontends are created, first and foremost, in standardized and automated way.

In this architecture, you want to have separate codebases and release processes for every other logically separated piece of your application — naturally you’ll end up with tens or hundreds of them. We needed to take control over this scattered landscape, and we couldn’t make it without standardization of all these moving parts and automation of interactions between them.

Let me now walk you through different areas that need this kind of treatment and how do we apply it to them.

Automated project creation

Let’s start from the beginning of the development — creation of new project. When your application is split into several micro applications by design, chances are that you’ll end up creating new projects quite often. Therefore, taking example from our colleagues from backend side, working in matured, service-oriented approach, we created tool for automated project creation.

Using this tool, developer can automatically generate standardized foundation for new microfrontend in one or two minutes, providing only a few basic configuration values along the way. As a result, he’ll get new code repository and new build and deployment plans connected to it.

When I say standardized build plan, I mean common process in which we take the code as it is on developer’s machine and process it to the form that can be served to end users. It involves compilation (with Babel), minification and bundling (with Webpack), or unit testing (with Jest), among other steps.

When I say standardized deployment plan, I mean common process in which we put this built code on certain environment. One important thing to note when it comes to our deployment plan: during automated project creation, developer can select whether he wants to have this microfrontend deployed as NodeJS-based service which renders the interface on server side and serves it as HTML to the user, or if he’d rather have it handled on the client side — then it’s deployed as static asset to one of our CDNs.

Application skeleton

The last piece that our developer gets out of this tool is code repository. It is not empty, though — there is application skeleton waiting there, ready to start development. There are some common tools encapsulated in the skeleton, such as linters for ensuring standard code styling, or build and deployment scripts. But it’s not the most important stuff.

Dan Abramov concluded his Twitter thread with realization that microfrontends architecture is directly related to Web Components API. With this API, one can define basic structure of UI component in vanilla JS, and have it implemented under the hood in pretty much any way he likes. This, in turn, enables teams to be autonomous in choosing not only some minor libraries and solutions, but even the most basic technology that renders their components — be it React, Angular, Vue, or whatever else is hyped and trending at given moment.

This conclusion seems to be natural especially when we take into account analogy to service-oriented architecture, where such practice is quite common. However, it’s important to note that most of the time different backend technologies are employed because there are vastly different tasks to accomplish — for example, one service is supposed to provide simple set of data as quickly as possible, while another’s assignment is to conduct some advanced calculations — and there are certain languages and libraries that are the best fits for the job.

On frontend side, on the other hand, at least in our case, our micro applications are doing the same job, and it is to display more or less sophisticated interfaces built from, after all, rather standard web elements. We couldn’t find reason to diversify our technology stack, other than developers’ preferences. But we’ve seen plenty of pros of going for one, shared technology stack. So that’s what we did.

Therefore, our application skeleton contains set of our standard libraries — React, TypeScript, Webpack. Having standardized tech stack enables us to cooperate above teams, share knowledge and solutions, not reinvent the wheel all over again, for every other library. Our developers can switch teams and projects as they find convenient. Performance of our website is also beneficent of this decision — we ship to our users only one library to render all pieces of the interface.

This decision also enabled us to go one step further and create standardized, shared frontend vendor package. There is React and all other common libraries we’re using in it. Vendor is loaded and cached once, at the very top of the first StepStone page you’ll visit. None of our microfrontends ship those libraries within itself — they all are based on assumption that those libraries will be provided externally. This way we truly load React only once.

Styling

Another common problem that we solve in standardized way, with tool shared across teams, is styling. It depends on the case if this approach makes sense, but my guess is that for most of the applications out there it does. Most of them, similarly to ours, are consistent when it comes to look and feel of user interface across different views and pages. If that’s the case, why define the same shade of blue or red in each one of your microfrontends separately?

As a matter of fact, we had shared styling library even before we started migration to service-oriented architecture and then to microfrontends. Originally it was based on Sass and was meant to be single point of truth for styling of common elements. However, with time, it became single point of truth for almost all of the styling — as it turned out, cases when given class, variable, icon or image was used only once were quite rare.

We maintained this little monster for years. As it grew in size, it was also changed more and more often — on average once every 3 days there was new release. Ultimately, we managed to put over 130 megabytes of stuff in it, and over 100 megabytes of CSS only. Honestly, I have no idea how we managed to make it so bad, but we did it anyway.

One year ago, we’ve migrated to a different solution — one that was heavily debated in frontend community over last few years — CSS-in-JS, implemented with library named Styled Components. In this approach, styles of certain components are stored next to JS code of those components.

import styled from '@stepstone/dresscode-react';

const Example = styled.section`

padding: 0 ${(props) => props.theme.spacings.spacingXS};

background-color: ${(props) => props.theme.colors.accent};

font-size: ${(props) => props.theme.typography.fontSizeM};

`;They are based on theme property that comes from ThemeProvider – higher order component we wrap our applications in.

import {

ThemeProvider,

getThemeVariables

} from '@stepstone/dresscode-react';

const theme = getThemeVariables('stepstone');

ReactDOM.render(

<ThemeProvider theme="{theme}">

<Example/>

</ThemeProvider>

document.getElementById('root')

);With this approach, we managed to reduce shared styling code to few kilobytes of JSON-based themes. Such themes are perfectly human-readable, do not require any CSS or Sass knowledge, therefore can be fully developed and maintained by our UX designers, which makes a lot of sense, given our organizational structure.

{

"breakpoints": {

"screenXSMax": "767px",

"screenSMax": "767px",

"screenMMin": "768px",

// ...

},

"colors": {

"black": "#222222",

"grey": "#8e97a4",

"white": "#ffffff",

// ...

},

// ...

}On a side note, adaptation of this certain approach would be much more of a hassle if we were not using one library for rendering our components across teams. This decision made our lifes simpler on many occasions, another example being common library of components.

Library of components

Given consistency of our UI and shared styling solution, why not go one step further and share actual components? Of course, there are some cons — here comes yet another piece of shared code that requires alignments and maintenance — but we found much more pros in this case. There are tons of components that look and behave exactly the same way all over our application, so potential for reusability and reduced code repetitions was immense.

We started with setting up tools and processes. We decided to put all of our components in one repository, utilizing so called “monorepo” approach. This enabled us to establish and automate one release process for the whole library as well as conveniently use tools like Storybook, which provides separate GUI to browse and play with our components. Thanks to this, everyone, also non-technical people in our organization, can easily check what building blocks are available out of the box for their product and what they can do. Versioning problems caused by monorepo were solved using tool named Lerna, which enabled us to have separate version per each component while having them all in one repository at the same time.

In order to migrate existing components to library as well as to add new ones in future, we agreed upon certain process. We realized that more often than not, API of a component changes to some extent after it’s deployed to production. In development we often do not realize at least some of the requirements that become clear once it works in living product. Therefore, we decided that each component that is supposed to be shared among teams needs to be battle tested first.

Once it lives on production for some time and proves itself, it can be added to the library as a proposition. Then it is reviewed by other frontend developers, and after some tweaks here and there, merged and released as a part of new version of the library. After this happens, its original creator is expected to switch it in his project from his own implementation to the one taken from the library.

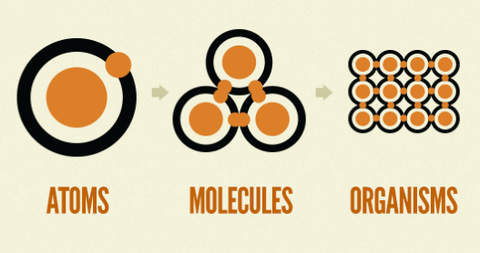

Additionally, in order to have those components conveniently cataloged and categorized, we decided to split them into atoms, molecules and organisms, utilizing concept of atomic design. Example of atom would be simple button or icon, while button with icon would be molecule — component built from two basic components. Example of organism would be customizable sticky bar — element that sticks to top of your page as you scroll down — consisting of several buttons, icons, buttons with icons, and other atoms and molecules.

Having common solution for styling and library of reusable components, we’re going towards fully blown design system — system, which is created together by frontend developers and UX designers. Currently our UX team has their own library of components, in this context understood as conceptual elements of user interface with well-defined purpose, not as their actual implementations in React. But those two things don’t need to be separated, actually it’s the opposite — it makes perfect sense to merge them into one, remove redundancy, and work on them in close cooperation. I believe that with tools I’ve mentioned, we have foundation for this kind of solution already in place.

Of course, you can have all these things while working on an application built in pretty much any other architecture I can imagine. It’s just that with this particular approach you absolutely need them, and you need them done good — otherwise you can’t effectively tackle unavoidable issues caused by fragmentation of development processes.

It’s no different when it comes to testing, which is the last aspect of frontend development that I want to touch in this article.

Testing

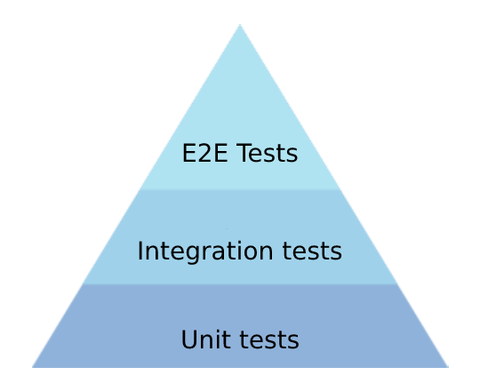

Testing is another place where you’d like to have different teams align and cooperate in order to create standard, common solutions. You want to avoid some teams forgetting to test their software, or omitting this step when it becomes inconvenient, or having different teams deliver software of different quality. Luckily, having all projects created with automated project creation tool I’ve mentioned before, we can relatively easily take care of at least bottom part of this well-known tests pyramid.

Standardized setup for each project means that each one of them is based on the same, standardized build and deployment plans. Having single source of truth about these processes, you can ensure that, for example, in every build unit tests are actually executed, or that the package will not be built successfully if certain amount of code is not covered by such tests. You can even make the process more sophisticated, including performance or accessibility tests in it — an approach we’ve not adapted yet, but are strongly considering.

However, need for alignment on testing techniques and processes is especially true when it comes to pinnacle of tests pyramid, so end-to-end tests and, to lesser extent, integration tests. After all, microfrontends are built in isolation. Therefore, solid and disciplined testing of their interactions in broader context is especially important.

As a matter of fact, we’ve got this part covered long before we decided to break down our monolith. Even back when whole application was still in one repository, we had whole another repository, so-called Automated Tests Framework, with rich collection of end-to-end tests written in Selenium, which we’re still using to this day. The only thing that changed due to transformation to services and microfrontends was that we’re not running all of them with every release. Instead, before certain part of user interface is released, we run subset of tests related to this particular part.

It’s important to note that none of those things means that teams can’t take more control over testing of their part of the application. Actually, it’s the opposite — standard test processes are baseline that has to be met, and teams are encouraged to add more layers of testing of any kind wherever they think it’s needed. In some cases, we have teams writing additional tests using tools of their choice, such as TestCafe, Galen, or Cypress.

Maintenance

There is one important lesson we’ve learned from our experiences with Automated Tests Framework. Similarly to automated project creation tool, common styling, or library of components, ATF is some kind of tool that is shared across teams. Those tools are meant to work like open-source libraries, in a way that they are maintained and developed by community of their users and on a basis of open discussion and contribution.

However, if maintenance of those tools is left to everyone, effectively they are not maintained by anyone. They tend to degenerate very quickly, stop being updated or cleaned up, stop working properly, and eventually stop being used. Our colleagues from quality assurance were aware of that long ago — therefore, they appointed specific, dedicated owner to their Tests Framework.

We call such owner a “custodian”, after Martin Fowler’s blog post on similar matter. Initially custodian of Tests Framework was one person, and as the tool was growing in time, more people were added.

Nowadays we have separate Automation Team, which is responsible for maintenance of ATF, among other things. It doesn’t mean that it doesn’t work like open-source software anymore — in every development team there is Quality Assurance Engineer who contributes to this framework on a daily basis, mostly focusing on his area of the domain, while team owning this tool reviews those contributions, provides feedback for them, and takes care of general housekeeping stuff.

There are plenty of shared tools in our microfrontend architecture, existing in order to standardize and automate our frontend development and avoid many issues caused by its fragmentation. Issues that will be avoided only if these tools are used, and they are going to be used only if they work for our developers — actually improve their developers experience and efficiency, not cause them more troubles. Hence, there is great need for clear and dedicated ownership over each and every one of these tools.

Most of them are simple enough to be owned by one person each. Custodian of such tool is not necessarily working on it full time — it might be specific person in regular product development team, dedicating a few hours per week for housekeeping purposes. What is important is that said person is committed to this task, and that others are well aware of this person’s role and processes set up by him or her. So, again — need for communication and alignment between developers from various teams.

One particular approach we’ve found working for us when it comes to appointing and communicating tasks of this kind, as well as aligning on any other decision related to standards in our development or our shared tools, is establishing a community of frontend developers with some well-defined communication channels. In our case, community consisting of frontend developers from around 15 teams meets weekly or bi-weekly to discuss and decide upon all of these topics I’ve touched today, and more.

Most of the time developers know very well what issues do they have in their daily work and how they could be solved. It’s just a matter of taking them out of their team’s context once in a while, facilitating discussion, helping them realize that others face the same problems, that those problems can be tackled on more general level, and eventually enabling them to work on some solutions during their work time. With this approach, our Frontend Community created most of the tools and solutions I’ve mentioned in this article and effectively facilitate our ongoing transformation to microfrontend architecture over past two years.

Summary

That’s it, when it comes to our journey through microfrontend architecture done in StepStone way. To sum up all of this, I’d like to repeat — microfrontend architecture, as any other architectural style, is just a tool (although quite sophisticated one). It’s good for the job it was design to do, and not much more. And it comes with clear, well-defined pros and cons.

Complexity of the whole setup and very high entry level are among cons of microfrontends. Delicate balance between teams’ autonomy in development and standardization and automation is very important and cannot be disregarded. Giving full autonomy to each team will end up very, very bad — but so will giving too much constraints. Additionally, it’s very likely that your project doesn’t need this kind of approach — it solves issues faced by large-scale applications which user interface is built by tens or hundreds of developers.

However, if you in fact need to scale your frontend by decomposition, and if you manage to set it up in standardized and automated way, you can achieve fast, agile, continuous development of large-scale application; you can benefit from possibility of progressive refactoring; and you can, in controlled way, empower your developers to take full ownership and responsibility of their code.

Because of those, microfrontends were employed in my project, and they work wonders for us. We’re still at the beginning of this journey — many more years of experience in different environments are needed in order to evaluate and validate microfrontend approach — but we’re confident that it’s the right path for us.

With more and more responsibilities being passed from backend to frontend side of our applications, and with more and more emphasis being put on seamless and sophisticated user experience, we, frontend developers, will face more and more complex problems to solve. Inevitably we’ll need more and more refined and intricate tools to solve them, and not only on frontend code level, where we did quite astonishing leap in the last few years, but also on more general level of frontend architecture. For me microfrontend architecture is direction that is worth exploring.

This article is published in installments, and here’s where the last one of them ends. Previous parts as well as additional learning resources are linked below.