In StepStone Services we’re working on maintenance and development of big, complex job board platform, among other things. This project was initially conforming to monolithic architecture and stayed this way for many years. However, in order to fight certain issues caused by such approach, service-oriented architecture on backend side and microfrontend architecture on frontend side were employed. In this article I describe our way of doing microfrontends, things we’ve learned from it so far, and tools and techniques that help us create and maintain this sophisticated software architecture.

Introduction

I joined StepStone Services four years ago as a software engineer in order to work on maintenance and development of our core product — online job board. You know, this kind of website, where user can search for interesting job offers based on some criteria, browse them, read them, apply for them if he wishes, and much, much more.

Project turned out to be a little bit more complex than I expected — both in terms of business logic and number of functionalities, as well as in terms of technical solution and architecture. Basically, it was one big repository with a few millions lines of code, written without too much attention paid to code separation, modularity, or readability.

I bet you know this story — either from your own experience, or from plenty of similar cases described all over the Internet. When I joined this project, the power of spaghetti was already strong in it. We only made it stronger, adding more and more layers of macaroni on top. With time it became harder and harder to add a feature without producing a bug, releases took more and more time, platform became less and less stable, and eventually we got stuck.

Back then it took us one whole week to put new version of our application from developers’ computers to our end users — we had one release per week. Nowadays we can put pretty much any piece of business logic or user interface from developers’ computers to production in less than 30 minutes, of course not omitting any of standard release process steps, such as integration or end-to-end testing. We managed to do this with — as a matter of fact still ongoing — transformation from monolithic to service-oriented architecture, but it wouldn’t be possible to do it fully without extending this idea to frontend development. And that’s what this article is about — extending idea of service-oriented architecture to frontend development — an approach often named “microfrontends”.

In this article I’ll walk you through this topic step by step, one problem at the time. I’ll start with defining terms “microfrontend” and “microfrontend architecture”, explain what’s the idea behind, and discuss pros and cons of the approach. Then, I’ll move on to more technical part, where I’ll show you how does it work in real life, how do we do it in my project, what are main pain points and how do we tackle them in our daily work.

What is a microfrontend?

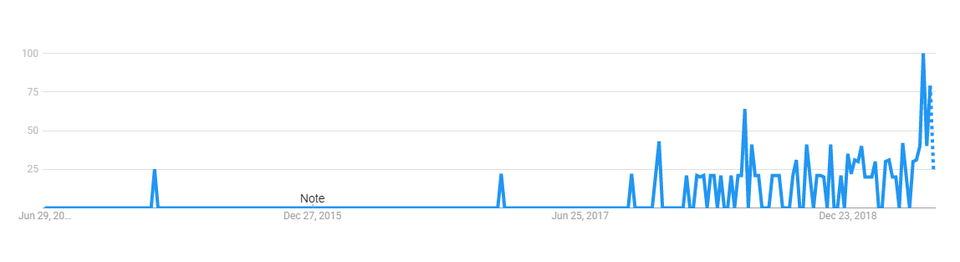

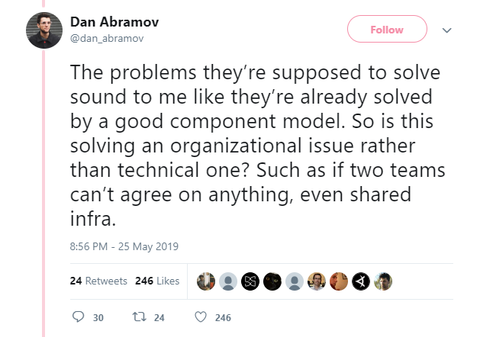

You might have heard this term “microfrontend” already — despite it being first used back in 2015, especially in 2019 it became yet another, trending IT buzzword on the Internet. It’s popular enough to attract attention of the most prominent of our fellow programmers, one of them being Dan Abramov, who tweeted in May of 2019 that he doesn’t understand the concept. This tweet sparked long and exhausting discussion on Twitter as well as served as a reference for plenty of articles, blog posts, vlog videos, or conference talks. Not surprisingly — discussion it originally prompted was very fierce, plenty of well-known experts voiced their opinions, and many important issues were raised and talked through.

I too will refer to this Twitter thread here and there in this article, as I want to address some of the issues that were pointed there. Let’s start with the first one — what is a microfrontend and what is all the fuss about?

As I mentioned, idea of microfrontends is direct extension of idea of service-oriented architecture to frontend development. Therefore, analogically to service or microservice, microfrontend is small, logically separated part of your application, or more precisely, in the context of frontend development, part of user interface of your application. Part, which first and foremost is independent from the rest of your system in terms of its deployment. Additionally, microfrontend should encapsulate some piece of business logic of your application and should be solely owned by a team that is responsible for this part of your application end to end.

Microfrontend architecture would be then an architectural style where independently deliverable frontend applications — microfrontends — are composed and served to the end user as one, complete, coherent application.

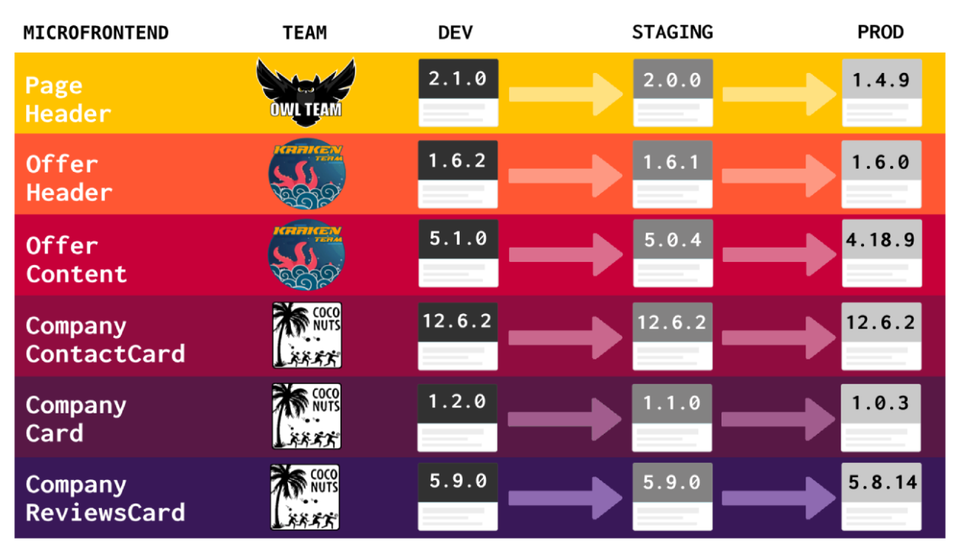

Application created with microfrontends approach to the end user may look like regular website, while under the hood it may be built as a composition of separate micro applications. Each of those applications has its own codebase and code repository, its own pipeline to push this code through from environment to environment, its own version on each of those environments at any given point in time, and its own team responsible for this area end to end.

The idea of code separation of this kind is nothing new — only in relation to frontend web development there were similar approaches described in the past, such as “vertically decomposed applications”, “self-contained systems” or “microservice websites” — but with rise of service-oriented architecture and microservices in last years, this approach, this time referred to as “microfrontends”, is getting a lot of traction and is being widely adapted. You can find plenty of talks and articles from past year or two coming from such companies like Microsoft, Spotify, or Zalando, where they describe their experiences with development of their products with this architecture.

If they are doing it, they are doing it not without a reason. But what might be the reason, then? Well, I can’t speak for them, but I can and will tell you why do we in StepStone do microfrontends.

Why do we do microfrontends?

Coming back to Dan Abramov’s tweets, he suggested that problems solved by this approach should already be solved by something simpler, such as good component model, hence it must be about something else. Maybe solving organizational issues? I partially agree with that. In our experience it does not necessarily solve any issues of this kind, but requires specific setup on organizational level by design, which you might find beneficial.

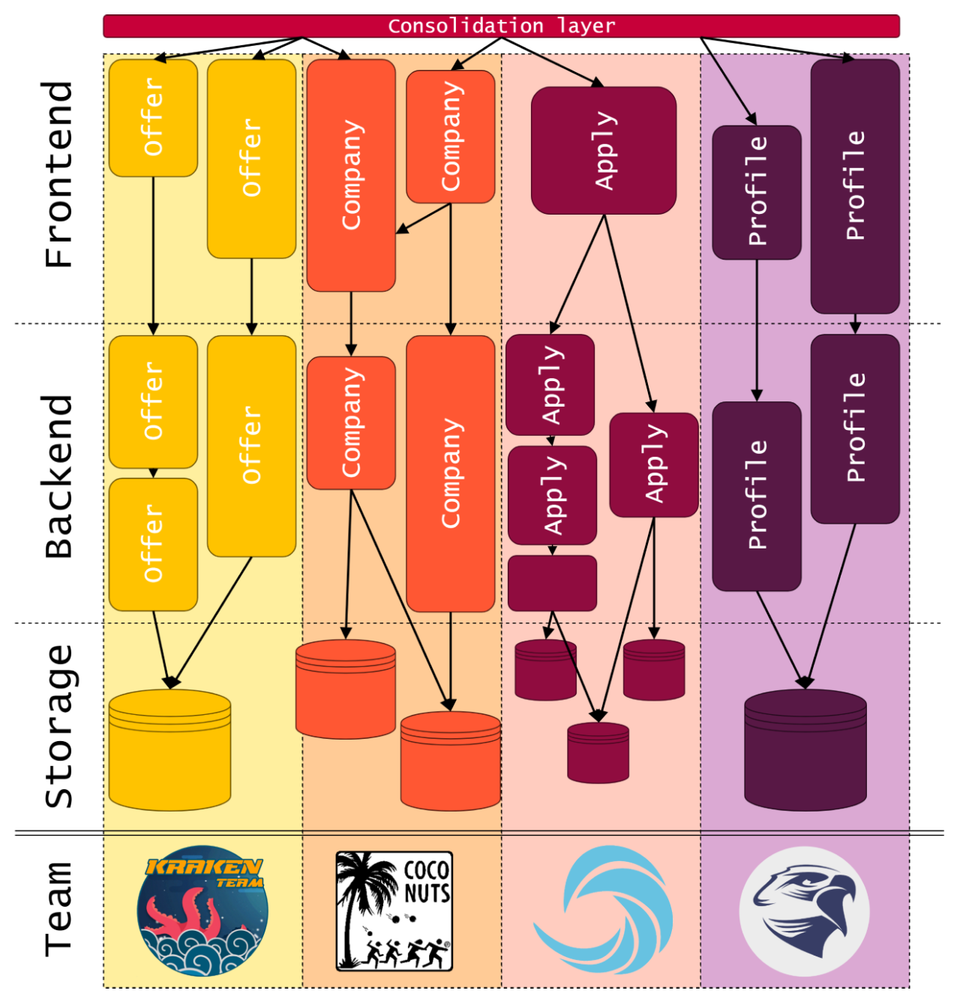

Let me show you what I mean. Assume an application, which consists of independent storages dedicated for backend services, which are then connected to their own frontend services, and then there is this thin composition layer on top of everything. This is how architecture of application I am working on looks like, of course represented in very, very simplified way. Once we put it in the context of our organization and add teams to this diagram, some of the benefits of this approach become very clear.

As you can see, given such separation of code, separate areas can be owned end to end by separate teams. This means that you can have small, autonomous teams, which are heavily focused on customer. Almost every member of every team has some impact on actual end users and can observe it. This naturally increased dedication, commitment, satisfaction of those team members.

It also enables teams to work on greatly reduced scope. You see, in case of our application, business domain became simply too big for one person to know it all. Hence, we split it into narrow, logically separated areas — subdomains — and assigned them to separate teams to own them end to end. Now developers in each of those teams can actually become experts on their part of the domain. Having deep understanding of business-related and technical aspects of their area translates to much better quality of the code produced and solutions designed by such team.

Both these benefits combined with main assumption of this architecture — that you can deploy small parts of your application to live quickly and harmlessly — directly impact speed and agility of your development. Imagine you have small, focused team, full of experts on what they’re doing, that can ship stuff to production in half an hour. Such environment encourages small changes, often iterations, experiments — basically everything that is encapsulated in term “agile software development”. That’s what we want — to be agile — so that’s what we do.

Additionally, having your application logically separated by design, you can minimize risk that comes with inevitable replacing its parts with entirely new ones — you know all dependencies beforehand instead of discovering them during development. Thanks to this, we can gracefully, progressively refactor our application part by part, wherever and whenever it makes the most sense.

I want you to keep in mind a few things, while I’m bragging about all these pros. First thing is the fact that architecture is a tool. Tool, that is designed to address and fix efficiently some certain, specific issues. This tool works for us, because it addresses issues we have — it is not meant to be used by everyone, everywhere.

As a matter of fact, it’s rather common recommendation to start with monolith instead. Monolith is good, solid, most importantly simple architecture pattern, that just does the job. Truth is, most of the applications that are created today will never grow in size to the extent where they’ll need such scaling by decomposition.

When it comes to microfrontend architecture in particular, probably the most common issue that people point out is potential, harming fragmentation of development processes, technologies, solutions, and eventually of the application itself. The risk is that dramatic increase in teams’ autonomy will lead to decrease in effectiveness and lack of consistency of the application.

The risk is valid, if you ask me — we’ve experienced this issue ourselves, on plenty of different occasions. However, I find teams being autonomous and fully responsible for themselves to be a good thing — and our developers tend to confirm that this model works for them. There are ways to mitigate this risk, mainly standardization and automation of variety of steps in software development processes, that will be discussed later in this article. Basically, it’s about finding good balance between said autonomy of teams and common standards shared across them.

It’s also important to take into account balanced, sensible size of each microfontend. Contrary to some beliefs, which in my opinion make this risk of fragmentation slightly exaggerated, not every single piece of user interface has to be separate entity. Naturally, the more fragmented your application is, the more threatening risk that comes with such fragmentation becomes, but microfrontends approach can be applied with different levels of fragmentation, which is another way to manage this potential liability.

How micro is microfrontend?

In short, microfrontend should be as small as it makes sense. As with service-oriented architecture, also microfrontends come with clear trade-offs. Smaller entities are easier and faster in deployment, but slicing one entity into several ones means need for more deployment processes, automation, integration, and also more dependencies between them. One big entity is easier to maintain as a whole, but comes with the cost of lack of separation — it may become less readable, take longer to test and deploy, or combine different logical areas in itself, leading to lack of clear ownership.

In our system, we have microfrontends that greatly vary in size. Most of them are small, single widgets — tens of which would be combined into one view — but there are also plenty of examples of microfrontends that represent whole pages or even collections of pages that are logically related to each other.

When we decide upon size of microfontend, we take several factors into account.

Reusability

First question to ask would be: “does this element is meant to be reused on different, separated views?”. If yes, it’s not worth to duplicate its code in all these places. Instead, it should become separate entity with single source of truth and integrated into those views separately.

However, it’s quite common that it’s not exactly the same microfontend across different views, but rather some kind of variation about it. In such case we make decision based on amount and severity of those differences. For small differences between variants we keep them as one and make varying elements configurable. The more configuration is needed, the more different variants are, and the more likely it is that they should be separate microfrontends instead.

It’s also important in this case to consider context in which this part is going to be used by others. Main question is if you, as an owner of such element, want to provide single source of truth about it — then you’re in full control of which of its versions is used by all consumers, but you’re responsible for making it work for all of them — or you want to give others a choice — then you pass this responsibility to them, but you can’t control which version they use and can’t make them migrate to the newest one whenever you find it ready.

Ownership

Another reason to create separate microfrontend would be based on answer to the question: “does this element extend across different logical areas owned by separate teams?”. If yes, it breaks the rule of single, clear ownership, therefore should be split into smaller elements, each assigned to specific teams responsible for corresponding area.

It is important for each microfrontend to be owned by single team which is keen on logical area related to this microfrontend. However, with time, we often add more and more functionalities to our widgets and applications, and sometimes they end up combining features from different areas. Once we realize that given element includes business logic that should be some other team’s responsibility, it becomes good candidate for slicing.

It’s rarely slice in half, though. More often than not it’s rather hierarchical relationship: we take part encapsulating such feature and make it separate microfrontend providing this functionality, pass ownership to other team and put it within their space, then refer to it from main applications, which becomes kind of consumer.

Usually we are aware of this kind of situation before this code is shipped to production — to realize that you’re developing outside of your area of expertise doesn’t require any magic. Hence, we try to do it the right way from the beginning, which means requesting such functionality from team responsible for area that it’s related to. However, it might not be possible to obtain it in reasonable time — after all, they might be busy doing other stuff.

Then we can implement it for them, as good as our limited knowledge allows us, and put it directly in their infrastructure by creating pull request. It still requires some work from them — to review it and to propose improvements, most likely more than few, since we’re developing in their area and attempt to conform to their standards — work, for which we also would have to wait sometimes unacceptable amount of time.

Therefore, such candidates for split are being created, and we’re perfectly fine with them, as long as they are marked as technical debt, which we transparently plan to pay off in foreseeable future.

Sheer size

Last but not least, there are candidates to break down into smaller entities due to their sheer size: “does this element start displaying problems similar to those that monolith applications have?”. If yes, that’s yet another reason to consider splitting into separate entities.

Some of our applications don’t have any elements that will be reused and fit perfectly into single team’s responsibility, yet we break them down into smaller ones due to the fact that their development and maintenance start becoming an issue. It’s entirely subjective metric, based on developer’s gut feeling and some statistics, most often related to scaling or releasing of this piece of software.

In other words, if we plan to scale certain part of microfrontend differently than the rest — for example, one part of the application will be accessed in run-time by 1 user per minute, and other by 1000 users per minute — it’s best if those parts are separated. If releasing becomes problematic, takes a lot of time, results in some bugs and generally becomes unreliable — it’s also best to split this element into smaller ones, although in such case it’s less obvious where to draw lines.

In practice

Good example of highly fragmented parts of the application would be homepage or dashboards of some kind — they often combine elements that are also visible on other pages.

Example of simple single page application would be, in our case, user’s profile edition page. It’s one page with multiple editable sections, where user can provide different kinds of information related to his education and professional career. It’s one whole app, none of its parts is used on any other view, fits into single team’s responsibility, and we don’t observe any issues caused by its size.

Finally, there are single page applications which encapsulate plenty of pages — such as editor of job offers, with which recruiters can conveniently set up all kinds of content that are later browsed by job seekers. This application is much more sophisticated than user’s profile edition page, as there are much more kinds of information to provide. It comes with plenty different pages and its own routing. Still, in our architecture it is one microfrontend — not reused in other parts of the system, owned by one team, released as a whole.

Of course, none of those examples is bound to stay in such shape in future — their size is based on their business requirements and whatever we find working for us in development and maintenance at the moment. Requirements will change, environment will change, our preferences will change, so setup of particular microfrontends will change too. We need to take into account all we know when we start, and employ the simplest possible solution. Therefore, as with architecture of whole application, also with specific microfrontends we usually start with small monoliths, unless we know beforehand, that there are requirements for reusability, cross-team features, or other contraindications.

All in all, there is no golden rule when it comes to size of microfrontend, and don’t trust anyone telling you that more “micro” or more “macro” frontends are better. Trust yourself and your judgement. Weigh pros and cons and decide upon slicing given part of your application into smaller ones whenever you find it beneficial to you.

This article is published in installments, and here’s where first one of them ends. In the next part you’ll read about actual technical solutions we are using in order to make this whole architecture work.